Rosario export hub able to ship 166 M tons of grain per year

Along the 70 km of coast on the Paraná river that go from the town of Timbúes to Arroyo Seco, called the Rosario city agribusiness node, a total of twenty-nine port terminals operating different types of load can be found. The majority of these terminals (twenty-two, to be precise) are equipped for loading grains, oils and/or by-products. From these terminals, more than the whole annual grain production of the country can be loaded.

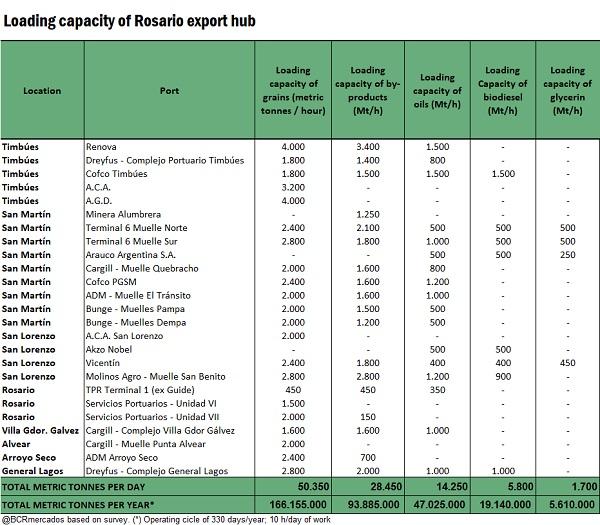

I) Load capacity of goods

All of the terminals surveyed can load unindustrialised grains, except for the plants of Arauco in Puerto General San Martín and Akzo Nobel in San Lorenzo, which are used exclusively for loading oil and biodiesel (in the case of Arauco, it is also used for loading refined glycerine). As for the plant with the largest grain loading capacity, there is the Renova plant in Timbúes, with a loading capacity of 4,000 tons per hour, sharing the first place with the brand-new oil plant General Deheza, also located in the town of Timbúes, which has a similar loading capacity. In total, it is estimated that from the ports of the node 50,350 daily tons of grain can be loaded. This, making certain assumptions on the operation rate of plants, results in a total of 166 million tons of grains that can be shipped per year from Rosario node.

At the same time, Rosario industrial-export hub concentrates about 80% of the theoretical installed capacity of the Argentinian oil industry, which makes it necessary for the docks to have facilities that allow for the collocation of this production abroad. Seventeen docks were identified with oil-loading capacity on tanker boats, the one with the highest capacity per hour is also in the Renova complex in Timbúes, where 1,500 tons of oil can be loaded per hour. In total, the theoretical oil-loading capacity is estimated in 14,250 tons per day from the surveyed terminals, and an estimated total of 47 million tons per year.

In the case of meals/pellets and other by-products, it is estimated that a total of 18 terminals concentrate a daily loading capacity of 28,450 tons of these agribusiness products, a yearly total of 93,8 millions tons.

Also, 8 terminals are equipped for loading biodiesel; the one with the highest individual capacity is in hands of the COFCO company, at its Timbúes facilities (1,500 t/h), totalizing a loading capacity of 5,800 daily tons of fuel. Besides, four plants can load refined glycerine, with a daily loading capacity of 1,750 tons of product.

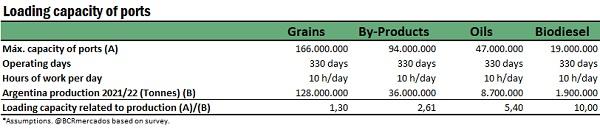

Thus, assuming a 10-hour per day work regime in these terminals, in an operative cycle of 330 days a year, we can estimate that from the ports of the region near 166 Mt of grains, 94 Mt of by-products, 47 Mt of oil and 19 Mt of biodiesel could be shipped. If we take into account production data for crop season 2020/21, we can estimate that from the terminals of Rosario city hub it could be shipped 1.3 times the national grain production, 2.6 times the production of by-products, 5.4 times the production of oils, and 10 times the production of biodiesel.

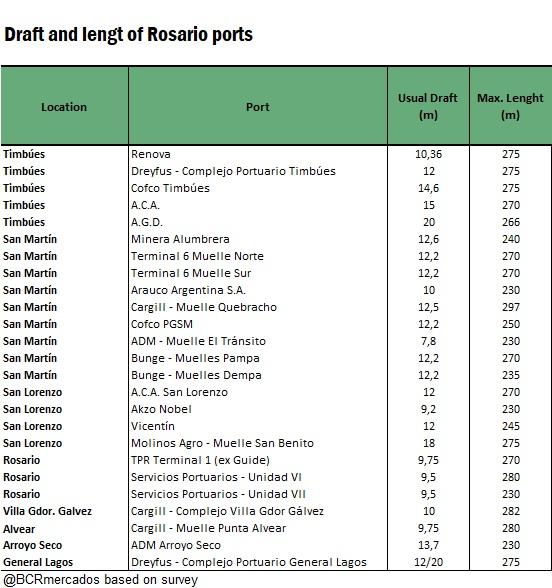

II) Draft and length

One of the main aspects to bear in mind when analysing the ability of port terminals for loading and shipping grains and by-products is the depth or draft of the ports in the area, which will determine the types of ships that can arrive and to which proportion they can be loaded. The limitations that are presented by the navigable draft of some river ports in our country cause that larger ships cannot complete their hold.

In general, under normal circumstances, the draft of the ports in Rosario exceeds for the most part 10 meters (33 feet) of depth, which allows for the entry of large-capacity grain vessels. The terminals which, at the moment of the survey, informed normal levels below this dockside measure were TPR Terminal 1, with 9.75 meters of draft, same depth as the terminal of Cargill in Punta Alvear; the terminal “El Tránsito”, property of ADM in Puerto General San Martín, with 7.8 meters of draft, and the AKZO Nobel in San Lorenzo, with 9.20 meters.

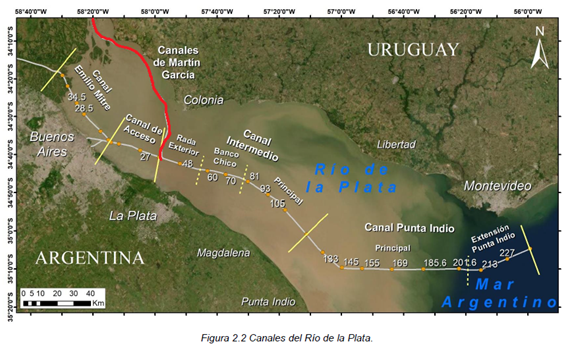

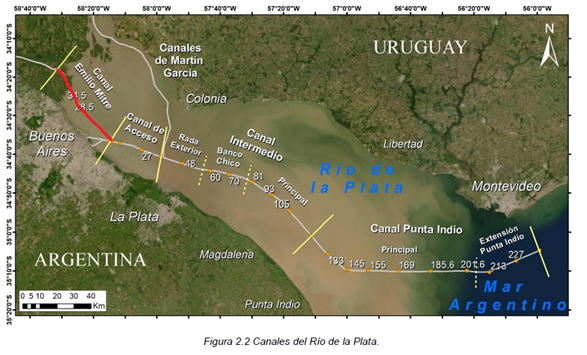

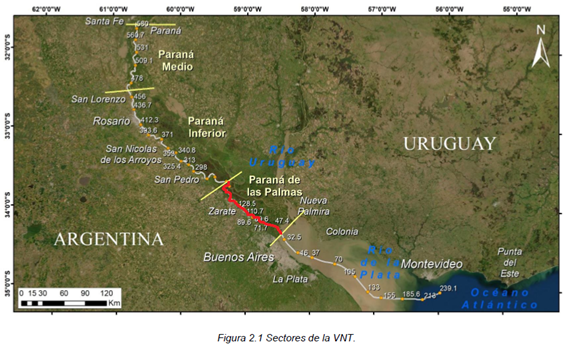

It should be born in mind that, in the so-called “Fluvial-maritime corridor” of the Paraná River, which goes from Santa Fe city to the ocean, two stretches can be distinguished in terms of depths: the first one from the city of Santa Fe to Puerto General San Martín-Timbúes, with a 25-feet design draft of the main canal, and the other one from Puerto General San Martín-Timbúes to the ocean, with a 34-feet design draft of the navigable main channel of the Paraná river. We need to clarify that this is the design draft of the navigable waterway, and does not mean that is the effective draft, which will be affected by the water level at each moment.

The other main determining factor for the type of vessel that can enter the navigable waterway and the ports in question is the vessel length. If the system limitations by maximum permissible length are analysed, two groups can be identified: per the physical characteristics of the Navigation Channel and per the physical characteristics of the dock infrastructure of each terminal.

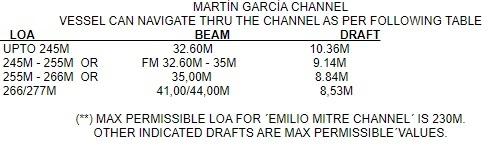

As for the length limitations per the characteristics of the Navigation Channel, we can distinguish:

I) Martín García Channel: the Martín García Channels can be navigated by vessels whose maximum length does not exceed the values expressed in the following table, according to the draft of the vessel.

II) Emilio Mitre Channel: the Emilio Mitre Channel can only be navigated by vessels whose maximum length does not exceed two hundred and thirty meters (230 m), except for the vessels that, due to their constructive characteristics, maximum drafts, stretch to sail in the Río Paraná de las Palmas, type of load transported, etc., have the corresponding proper authorization.

III) Río Paraná de las Palmas: in the whole area under consideration, only the vessels whose maximum length does not exceed two hundred and thirty meters can navigate (230 m).

Additionally, in each dock there is a maximum permissible length according to the physical characteristics of the dock. If we consider the terminals of Rosario node, they can go from 297 m of maximum permissible length in the dock of Cargill in Quebracho, with 230 m as the lower record on the docks of ADM – El tránsito in San Martín, ADM – Arroyo Seco, Servicios Portuarios Unidad VII in Rosario and Akzo Nobel in San Lorenzo.

III) Cargo share from the ports of Rosario and current situation

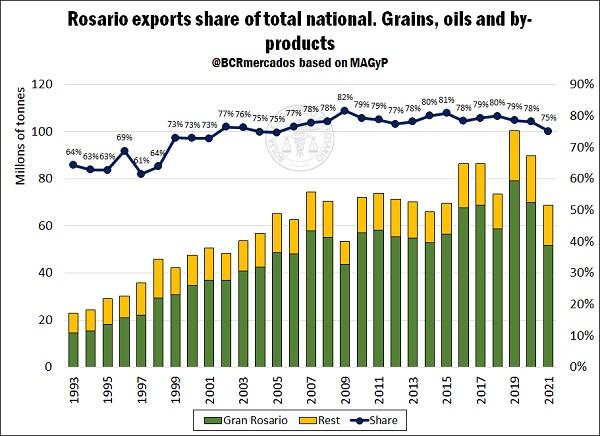

In a normal year, about 80% of the exports of Argentinian grains, meals and oils leave from the ports of Rosario, a share that has remained relatively constant during the last decade.

In year 2020, only from the ports in the area, a gross total of 70 million of tons of these products were exported. During that year, from the port terminals located on the Up-River Paraná ports, there were shipped 70% of the grain, 96% of the vegetable oils, and 96% of meals exported by the country.

We can see, however how the share of shipments falls in 2021 in comparison to previous years. This is explained, basically, by the unusually low water level of the Paraná river, which has particularly impacted Argentinian exports: the hydrometer located in Rosario reached in August a mark of 33 cm below zero, the worst record since December 1970.

The lower depth in the stretch Timbúes-Ocean affects the draft at which boats can sail and limits the loading capacity of the vessels that navigate the waters of the Paraná river, apart from forcing to redirect the load to other ports.

Among the impacts the shallowness of the river is having on the industrial-export node are the difficulties and extra costs of having to bring goods from the North of Argentina and Paraguay, the lower loading possibilities of grains and oils from the Rosario city region, the increases in the risk premiums over the FOB price for the export of oils and meals from Argentina, and several additional industry-insider costs due to the slowdown of the shipping rate. For further information on these issues, we recommend reading this article.

The drop of Rosario city share of exported volume can be mostly noticed in the export of cereals, given it is easier to relocate the cargo. That is to say, exporters can increase the origination of goods in Southern ports (for a cost overrun), which cannot be made in the products of the oilseed complex, whose productive matrix is in the ports of Rosario themselves from where they are shipped.

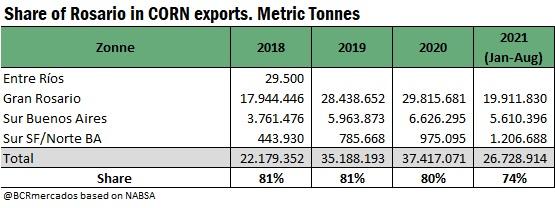

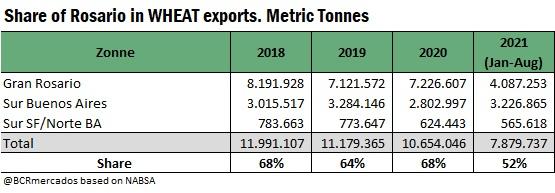

In the following chart we can see how the cargo share of the two most produced and exported cereals in our country has been reduced in the current year.

As it can be seen, in the case of corn, the share drops from a base of 80%, which had been constant in the three previous years, to 74% in 2021 to date. As for wheat, with a more distributed cargo with the ports in the South of Buenos Aires due to the localization of the national wheat production, the share in 2021 drops a bit over half of the total shipments.

In the future, a factor of concern is what could happen with a forecast of Niña event in the next spring-summer, which is a traditionally more rainy. This phenomenon is normally associated to rains below normal in key regions in the South of Brazil and North of Argentina that contribute to the water flow of the Paraná River which, if it is not recovered during these months, could severely affect the Argentinian agribusiness export logistics in 2022.