The phenomenon of above-two-digits year-on-year inflation in Argentina has already occurred for more than 10 years. However, between 2010 and 2020, the inflationary problem was virtually non-existent in the rest of the world. To mention a few examples, from 2010 to date, year-on-year inflation in Germany never exceeded 2.5%, in the United States, 3.9% and in Spain, 3.8%. Not only that, but even in several months of the last decade they registered a negative year-on-year variation in the consumer price index, which is commonly known as deflation. In Brazil, to mention the case of another South American country, there was a year-on-year inflation of over two digits during five months between the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, but it showed an inflation of less than 10% during the rest of the months of the last decade.

However, this seems to have changed since mid-year. Several of the main economies in the world have suffered an inflationary surge in consumer prices, although still much lower than the one experienced in our country. Continuing with the examples presented, the United States reported a cumulative inflation of 5.4% in the last twelve months in September, the highest since mid-2008. In Germany it was 4.1%, setting a record since at least 2004. Spain also suffered from this phenomenon, and in September reported a year-on-year inflation of 4%, the highest since 2008. In Brazil, in the meantime, the variation of the consumer price index in the last twelve months reached 10.8%, exceeding the double-digit barrier for the second consecutive month.

One of the causes of this phenomenon can be found in the accommodating monetary policy carried out by the vast majority of the world's central banks as a measure to alleviate the effects of the economic crisis unleashed by the coronavirus pandemic. But there is also another phenomenon that adds to the upward inertia of prices: the sharp rise in energy costs. In recent times, the prices of oil and gas (two prices that are considered basic in economics due to their influence on the production costs of other goods) have exhibited a strong increase and reached maximums in several years.

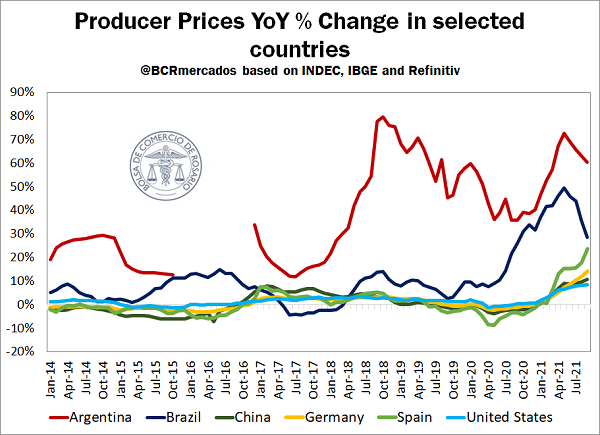

This translated into a strong increase of the Producer Price Index (which measures the monthly evolution of prices received by producers for products manufactured and sold in the domestic market) in all the countries under analysis. In the United States, the year-on-year variation of the wholesale price index in September was 8.6%, the highest since 2014; in Germany in the last month it was 14.2%, the highest record since at least 2004; in Spain, the September figure was 23.6%, the highest since 1977. In addition, there is also the case of China, which in the ninth month of the year reported a year-on-year rise of 10.7% in producer prices, the highest since at least 2005 (it should be clarified that, unlike the rest of the countries, the consumer price index in the Asian giant does not register a significant rise: the year-on-year variation in September was only 0.7%). In Brazil and Argentina, in the meantime, during recent months the increase in prices received by farmers has slowed down, but they remain considerably high. In September they grew 60.5% year-on-year in Argentina and 28.6% in Brazil.

It is evident that the producer price index shows a greater range of variation than the consumer price index. However, there is a close relationship between the two, and a question that arises is whether this increase in producer prices will translate into an acceleration in the rise of consumer prices in upcoming months.

On the other hand, as a base indicator of the income of these consumers, the minimum living wage (SMVM, for their Spanish acronym) in Argentina currently stands at $ 32,000, which equals US$ 179.8 if the CCL dollar is taken as a reference. This monthly income set by Resolution 11/2021 is well below the minimum wages in dollars of the countries of the region comparable to Argentina. Chile (US$ 414,0) and Uruguay (US$ 407,9), for example, more than double Argentina’s minimum wage; while Paraguay (US$ 317,0), Colombia (US$ 270,1) and Peru (US$ 232,8) also exceed it with a considerable margin. Of the selected countries, only Brazil’s minimum wage (US$ 194.6) remains, as in the Argentinian case, below the barrier of US$ 200 per month.

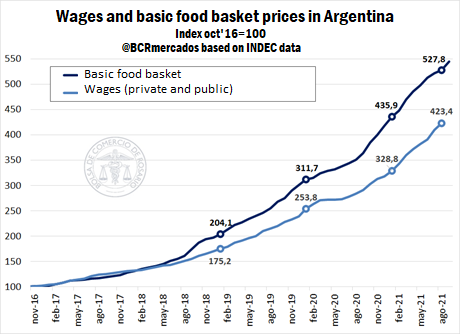

In recent years, the purchasing power of Argentine wages in the country itself has deteriorated significantly as a result of the deepening of a sustained inflationary process. The following graphic illustrates the loss of purchasing power of wages compared to the total basic food basket. For its construction, we used the registered wage index of private and public sectors, as well as the unregistered ones, published by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC, for its acronym in Spanish); and we calculated the index of the total basic basket, used to determine the poverty line, also reported by INDEC. Both indices have as a base period (=100) the month of October 2016.

In August 2021, the total basic basket index amounted to 527.8 points, while the wage index was over 100 points lower, at 423.4 points. The gap between the increase in prices and the increase in wages began to expand as of the first quarter of 2018, and the price control policies implemented with the aim of controlling inflation did not manage to shorten the distance. If these indices are compared at the beginning of recent years, as shown in the graphic, it is possible to distinguish the progressive deterioration of the purchasing power of Argentine wages. We should remember that those people whose income cannot cover the total basic food basket fall below the poverty line.