The Black Sea wheat, a benchmark that is consolidating in the international market

BLAS ROZADILLA - EMILCE TERRÉ

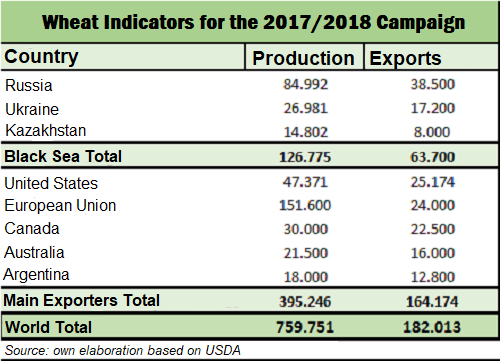

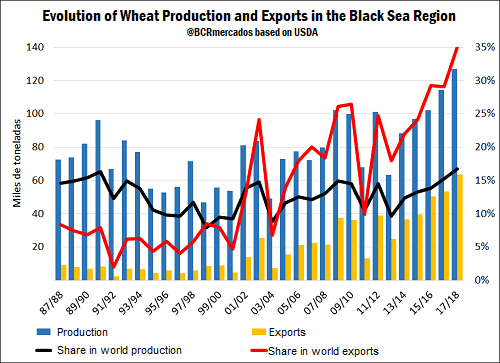

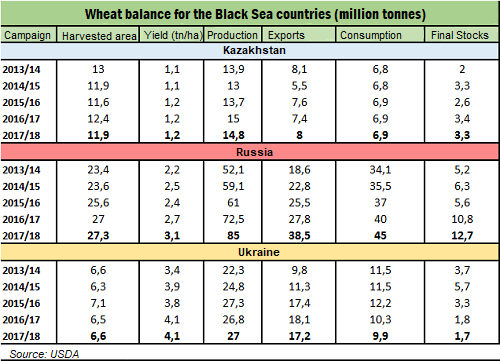

Since the beginning of the 2000s, the countries of the former Soviet Union that have access to the Black Sea began to increase their volumes of wheat production and, along with it, their exportable balances. This led to Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan (who make up the so-called Black Sea region) to position as the leaders in world cereal trade. The wheat production of these three large countries in the Black Sea region accounted for a greater proportion of world production in recent years. In the 2017/2018 cycle, the three countries of the Black Sea would have reached a total production of 126.7 Mt, which represents 17% of the world production estimated at 759 Mt. (see table below). This is a clear indicator of the relevance that these countries have acquired in the growing export business, as well as their greater relative importance in terms of supplying and maintaining the wheat stocks needed for the world. From a long-term perspective, it can be noted that combined wheat exports from Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan have grown faster than global exports mainly since the beginning of the century. That is why they have taken a greater presence in international trade, reaching, according to USDA's estimates, a 35% share in world exports for the current campaign. In the 2017/2018 season, wheat exports from these three nations would amount to 63.7 Mt over a world total of 182 Mt.

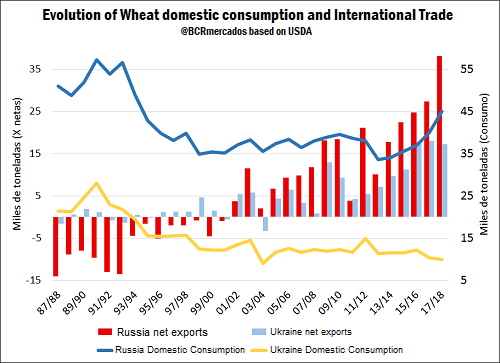

The transition from the Soviet socialist economies to market economies During the Soviet regime, economic planning entailed strong subsidies and price controls in the agricultural and livestock sectors, both of major importance in terms of food security. The government used to set domestic prices for primary products well above international levels while providing inputs at prices well below market values. This resulted in an over-expansion of the sector, making it very volatile to the conditions of supply, demand and international prices once those countries began their transition to a market economy. At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union between 1990 and 1991, the sudden and uncoordinated elimination of these price arrangements, together with the suppression of subsidies for the grain production sector, generated a state of uncertainty and continuous changes, that lasted until the new independent countries managed to adapt to the new conditions, and caused a strong impact on production. This new context was characterized by high prices of inputs (through a strong devaluation in exchange rates) and low grain prices (due to dysfunctional market mechanisms and lower demand for animal consumption). These conditions caused a significant contraction in agricultural production. In addition, the incentive scheme imposed by the Soviet regime did not lead producers to focus on efficiency or yield per hectare, exacerbating the problem. Ten years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the area devoted to grain production had decreased from a maximum of 125 million hectares, to a level of between 70 and 80 million hectares. Russia, leader in the resurgence of Black Sea wheat in the world Taking as a reference the case of Russia, the most important country in the region's wheat production and the one that boosted the positioning of the Black Sea region in world trade, it is observed that per capita meat consumption was reduced to half during the 1990s as a result of falling levels of income, changes in consumer behavior and the reduction of livestock stocks. With fewer economic incentives for farmers to maintain previous production, Russia's cereal production collapsed, as farmland in Russia was reduced to 41 million hectares between 1990 and 2011 (AEGIC, 2016, Menker, 2016). Despite the loss of subsidies and farmland, Russia emerged as a net exporter of wheat in the 2001/02 marketing year, thanks to the increase in exportable balances due to the fall in demand for animal consumption and the relocation of the sector in the new market economy that led to the rebound of investments and the purchase of inputs. Something similar happened with Ukraine, which, however, unlike Russia, was never a clear net importer of the cereal. Both were the two countries that have seen their wheat exports grow the most in the last two decades.

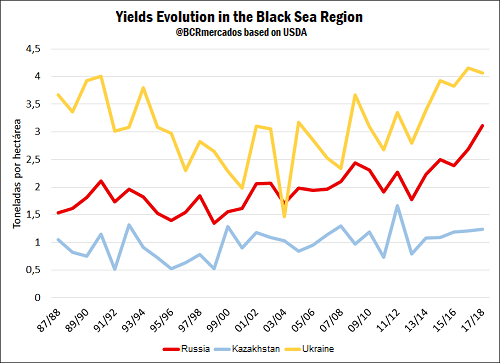

One of the main factors that triggered the upturn in cereal production was a change in government policy, which in 2005 increased funds for agriculture. In the period between 2005 and 2010, the Russian government increased its support to the sector, in real terms, by 135%, in addition to the additional support provided by the reactivation of the livestock sector. To boost the increase in the domestic availability of cereals, a tax on wheat exports was applied during 2008 and a ban was imposed following the poor harvest of cereals in 2010. These restrictions increased the domestic supply of cereals for households and the livestock sector. However, despite taxes and prohibitions, Russian wheat exports grew annually - on average - by more than one million tonnes between the 2002/03 and 2015/16 seasons (AEGIC, 2016). During this process, the government welcomed the process of foreign investment that led to the technological renewal of the sector and its vertical integration, through the appearance of agroholdings. The agroholdings began to appear after the change of economic regime, acquiring existing corporate farms and integrating them vertically, to then combine primary production, processing, distribution and, sometimes, retail sales (Gataulina et al., 2005, Serova, 2007, Rylko et al. al., 2008). In the graphs shown above, it can be seen that both production and exports from Russia and the region are highly volatile. Changing climatic conditions, which are reflected in yields, and changes in commercial policy translate into uncertain returns for agriculture in the absence of adequate insurance systems to protect against possible falls in production, on the one hand, and against the deterioration that the irrigation systems of the Soviet era have suffered over time, on the other.

Political decisions can largely affect the production and export of grains. Russia has a long history of using trade policies to protect the domestic supply of wheat and to combat rising food prices. During 2008, a tax on wheat exports was introduced, something that was repeated in 2015; After a bad harvest in 2010, a ban on external sales was imposed. These decisions reveal the crucial importance of self-sufficiency and affordability of food in Russia. From this it can be seen that Russian grain exports and their variability do not depend only on climate, but can also be the result of deliberate government action. In Ukraine, for six campaigns, the Ministry of Agricultural Policy and Food of Ukraine (MAPF) and representatives of local non-governmental organizations have come together to agree and sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on grain exports. For each commercial year, specifying the specific exportable volumes for wheat and other grains. The MoU is a non-binding document that establishes the exportable volumes of the main grains that MAPF considers fundamental for national food security. Initially it was designed as an instrument to balance public and private interests, and served as a viable alternative to other administrative instruments to intervene in the export market (such as prohibitions or export quotas) applied in previous years by MAPF to guarantee an adequate grains supply within the country. What is expected? The exporters of wheat from the Black Sea region have benefited mainly from their advantages in shipping costs to the main cereal importing countries in North Africa and the Middle East, compared to the costs and distances of the other exporters that compete in this market. Although the wheat of the region may be of a lower quality than that of other important producers and exporters (the protein standard is 11.5%), this is completely offset by its significantly lower price. In recent years, in addition, this was accompanied by a fall in the exchange rates in Russia and Ukraine, improving the competitiveness of their products in the export market and further increasing the price differential. However, infrastructure restrictions pose a limit to exports in the short term. SovEcon reported that roads and ports in Russia have been operating at full capacity in this commercial campaign, which will set an export record. To accompany the expected increases in agricultural production, the government has financed a greater port and storage capacity. There has been an increase in spending on infrastructure along the Black Sea. According to a report by the USDA's Global Agricultural Information Network, industry analysts estimate that the total capacity of Russia's grain export infrastructure is between 48 and 55 Mt. Beyond this, Russia's grain exports are limited also by factors such as the presence of ice in the Sea of Azov, cargo restrictions in the Black Sea terminals and trade barriers in the main countries of destination, making it essential to prioritize investment in infrastructure. On the other hand, improvements in the management of crops could minimize the variability of yields, giving greater predictability to the supply of the region. Final considerations The consolidation of the Black Sea region as the main reference in the international wheat market is a fact. The boost given by the growth in production and exports of Russia, have led the Black Sea countries to lead the change and reconfiguration of world wheat trade, capturing the attention of the operators of the relevant markets.

Although the climatic issues and the bottlenecks that can be generated by the lack of an infrastructure according to the volume of production, generate uncertainty and make the volatility in the export performance of the region; the existing potential and the approach of foreign investors suggests that the importance of the region in the world wheat market will nothing but grow in the coming years.